An Examination of Gates Thruston's Archaeological Work: Antiquities of Tennessee

Tennessee History Project Installment Four

An Introduction to Gates P. Thruston

Today, we are examining Gates Phillips Thruston’s Antiquities of Tennessee. Thruston is, and you will see our common theme emerging, a rather unknown figure. His Antiquities appears to be the first major archaeological study of the area in and around Tennessee. I’m not typically one for archaeology, but it never does hurt to have a background knowledge of something and there are worse ways to begin than this book. It is devoid of the anti-White and anti-Christian screeching that I have become familiar with at university and it takes its study quite seriously. I do not intend to subject the reader to minutiae about Indian artifacts and I intend instead to make general observations from the book readily available.

The copy that I have managed to procure is a 1964 Tenase Explorers reprint out of Knoxville. It was originally published in 1890 by the Cincinnati Robert Clarke Company under the title of The Antiquities of Tennessee and the Adjacent States and the State of Aboriginal Society in the Scale of Civilization Represented by Them: A Series of Historical and Ethnological Studies. I personally love 19th century titles. The outside of the volume bears the descriptor “second edition.” The difference between the second edition, which appears to be from 1897, and the original is that the second volume includes two supplemental chapters and footnotes about certain things that the author believed were mistakes. The original volume appears to have been dedicated to the Tennessee Historical Society.

The brief note at the start of the volume from Richard Myers and Beverly Burbage of the Tenase Explorers publishing house indicates that in 1964, despite the passage of time, the work was still the primary text on archaeology in the state. I once got a special tour at a certain museum and it would not surprise me if that is still true given the leftist policies presented on that occasion, which have been pushed, if I am not mistaken, by the Biden administration, of most museums to repatriate everything under the sun that an Indian claims to have rights to and which the museums may never dispute. It must be more difficult now to study such artifacts than it has ever been. And, as we shall soon find, this repatriation policy may not make as much sense as people believe.

I digress. As is becoming customary, let us examine some biographical details of Mr. Thruston. In brief, Mr. Thruston was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1835. His ancestors were of English birth, and they originally settled in Gloucester County Virginia in 1666. One of his ancestors was a Colonel Charles Thruston during the Revolution. He attended Miami University in Ohio and graduated in 1855 as valedictorian. During the War Between the States, he served initially as a captain in the First Ohio Infantry. He was promoted to Major by General Rosecrans for gallantry on the battlefield at Murfreesboro. In 1863, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and fought at Chikamauga, after which he was again promoted to brigadier general. After the war concluded, General Thruston remained in Nashville, where he married Ida Hamilton by December of 1865.

At this point, Thruston engaged in significant protest against the mistreatment of Southerners after the war, opposing military governance and the disenfranchisement of Confederate soldiers. He remained in Nashville for the rest of his life, retiring from the legal profession in 1878. He held the position of president in the Tennessee Historical Society for a number of years, during which he collected a substantial number of Indians relics that later found their way into the possession of Vanderbuilt University. He remarried in 1894 to Fanny Dorman before his death in 1912.

Obviously, this is not Thruston’s complete history, and I have linked further resources below. Now, for the content of the book. I am someone who knows almost nothing of the pre-colonial era in America. Thruston’s book largely focuses on the analysis of relics and sites, which is useful in its own right. But, I would very much like to expose some of his other observations. Here are Mr. Horn’s comments on Antiquities:

Stone Grave Indians and Problems of Indian History

Many of Thurston’s valuable insights are found in the introduction and conclusion, at least for our purposes. The book itself was written when a large Indian cemetery was discovered near Nashville. It began as a pamphlet after Thruston’s examination on behalf of the Tennessee Historical Society and grew into this work. Indian artifacts were so commonly found in the state, that several artifacts presented in the book had been damaged by plows, giving some indication as to the scope of what was once a bustling Indian region. The first fact, and most shocking for myself at least, that becomes apparent within the early parts of the text is that Mr. Thruston is not chiefly examining what we usually refer to as Indian tribes.

The mounds and cemeteries and artifacts under consideration belonged to an ancient race of Indians that he refers to as the Stone Grave race, or the Mound Builders. The scale of Indian civilization apparent in these graves had not existed for hundreds of years prior to settlement. Three thousand people were buried in the grave. For several generations, there was semi-civilization, but it was not there by the time our forefathers settled the land. Of all of the artifacts presented, they belonged to a people that had been extinct for a very long time. That fact alone is worth some meditation, as well as the implications of the significance of narrative salience by informational obfuscation.

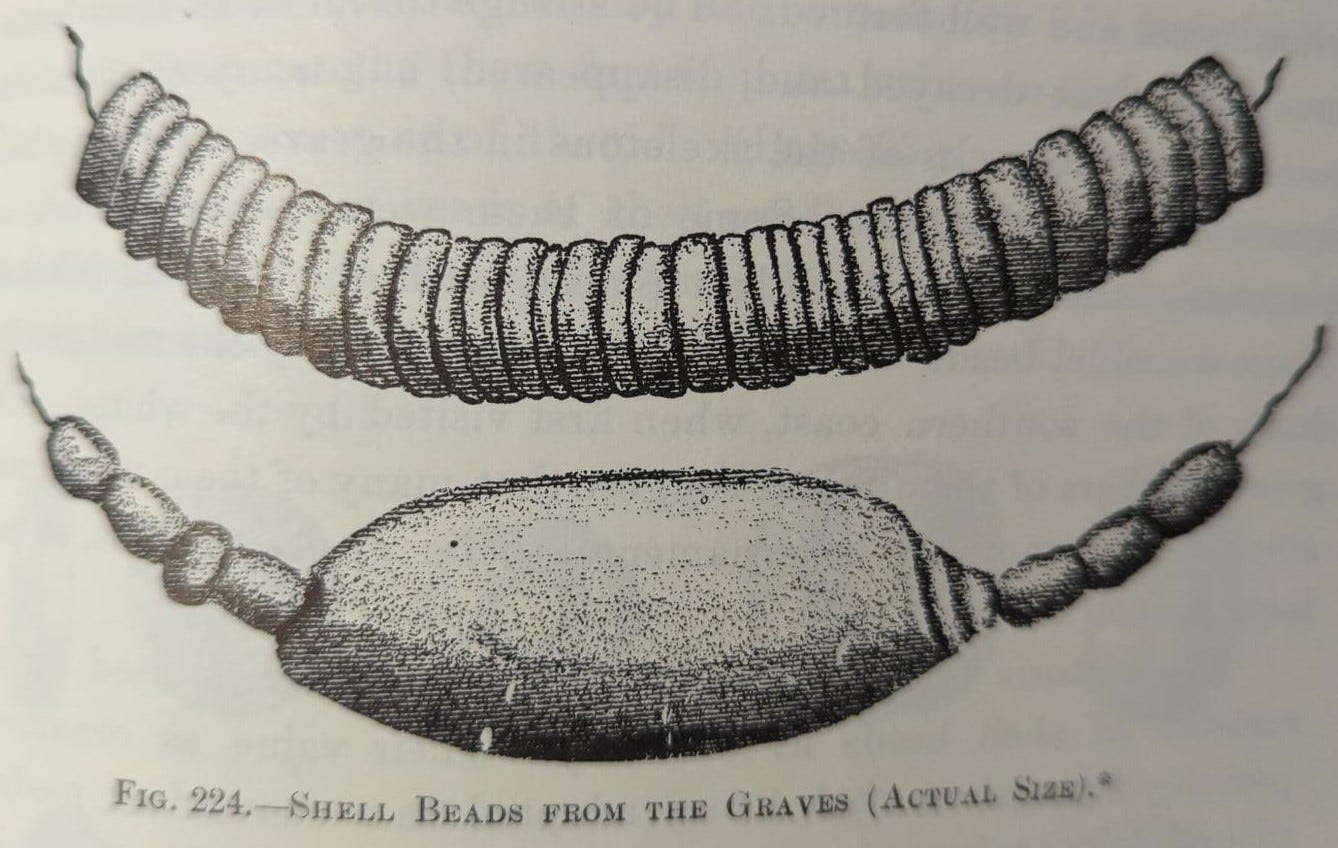

The next thing that comes across, is the breadth of this lost people. There were apparently networks of trade across many regions. At the Stone Grave site in Nashville alone there were materials from the South Atlantic Coast, Virginia, North Carolina, and even Western Minnesota. This group used a variety of bartering methods, most likely. It even had a kind of sea shell trade that approximated currency. Indeed, by the time of Adair, who wrote his own History of the American Indians, shells had obtained a fixed value.

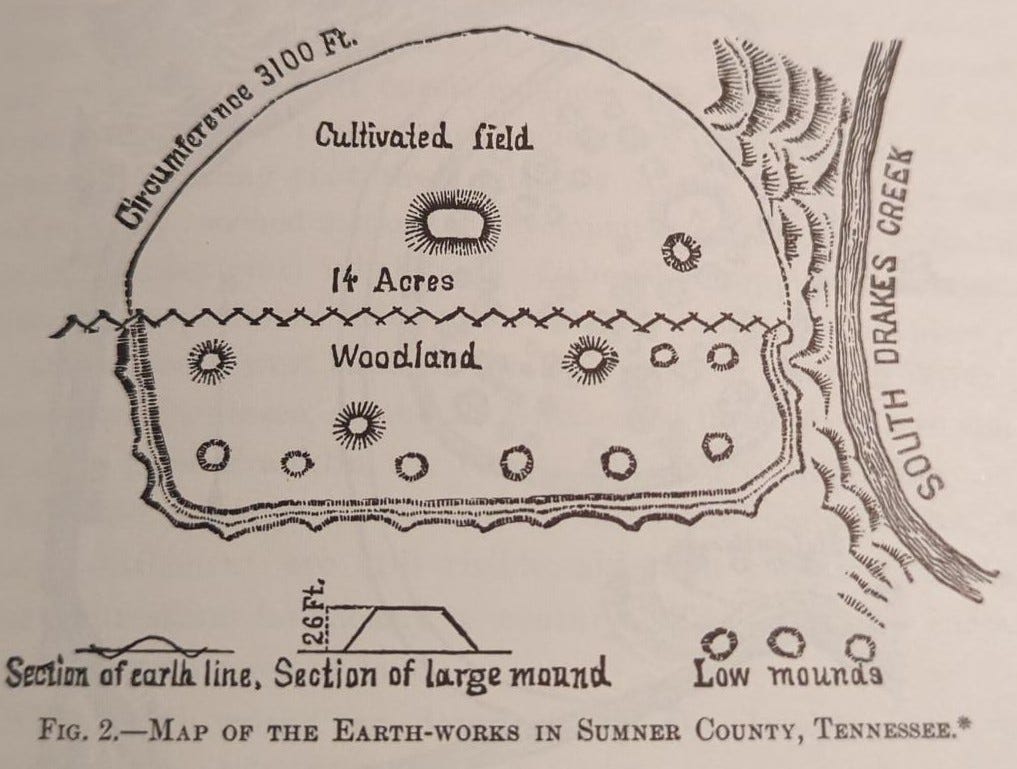

When it comes to the living conditions of this ancient people, they largely lived communally. Oftentimes they organized themselves on the basis of kinship. Villages, even cities, could involve serious earthworks and storehouses. Their homes could hold a great many people, and cities could contain hundreds of people in them. In many cases, large mounds were built up, as they were more defensible, and people could reside on top of them. There was even agriculture. Below is an example, out of many, of Stone Grave earthworks.

An interesting fact about the discovered cemeteries is that many were found in what were once areas of defense. They could be made of stone, even having multiple layers of protective walls. Within the area, there would be mounds for elevated defense, as well as the cemeteries. Thruston believes that the defenses may not have arisen until later stages of the land’s occupation. The Stone Grave cemetery in Nashville lacked such defenses, however there were defenses in the surrounding area. Thruston suggests that such forts were outlying defenses of the area’s population. It is possible, he argues, that these defenses only arose in necessary defense against the powerful neighbor that originally wiped out the Stone Grave Indians. Perhaps it was the Iroquois from the North.

But, in reality, very little can be know about their history. They had no written word. Indeed, a great deal of Thruston’s material is spent examining Spanish, French, and early English writings on interactions with the Indians. He has no other means by which to judge their practices. Journals from expeditions like De Soto’s in 1540 are the only gauge for the rise and fall of the Indian tribes in the area. Even then, it is uncertain whether or not the Stone Grave Indians fell before or after De Soto. By the time settlers began to move into the area, the semi-civilization that once existed had degenerated to such a state that the tribes encountered often could not even give explanation as to the relics and earthworks of what may or may not be their forefathers’ work. Even the manufacturing tradition of pottery and flints had declined as French tradesmen made inroads into the area before settlement and it was no longer necessary to produce flint when steel could be used.

Thruston marks the art, manufacturing, and practices of the Stone Grave people as descending from their Southwestern counterparts. Their culture and the fact that they had villages indicates a relation. Thruston and his colleagues engaged in analysis of skeletal structures, particularly of skulls, which seemed to indicate such relation, and a distinction from the Northern tribes. He reports that French explorers detailed the constant warfare among the tribes at the time. Owing to historical difficulties, Thruston could not discern the relation of the once grand Stone Grave race to the violent nomadic tribes of settlement, as they could have been forced out of the land and come apart nationally, been eradicated, or assumed. One of Thruston’s colleagues favors the idea that they may have been the ancestors of the Shawnees, having abandoned agriculture partially due to constant war and being driven to a far less civilized state. As Mr. Thruston notes: “Conquest and progress followed by degeneration and decay is the lesson of history.”

Notes on Some Aspects of Indian Life

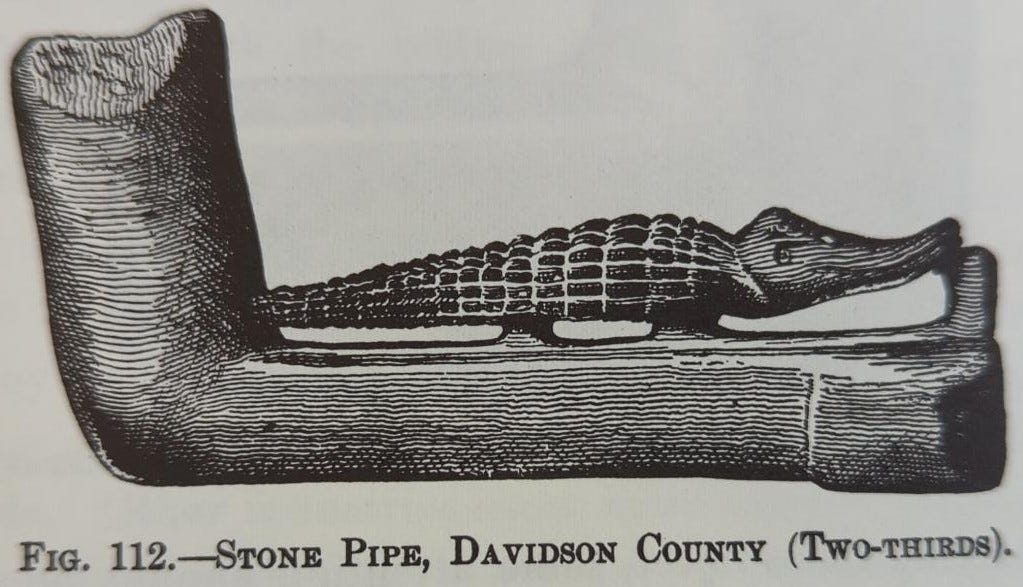

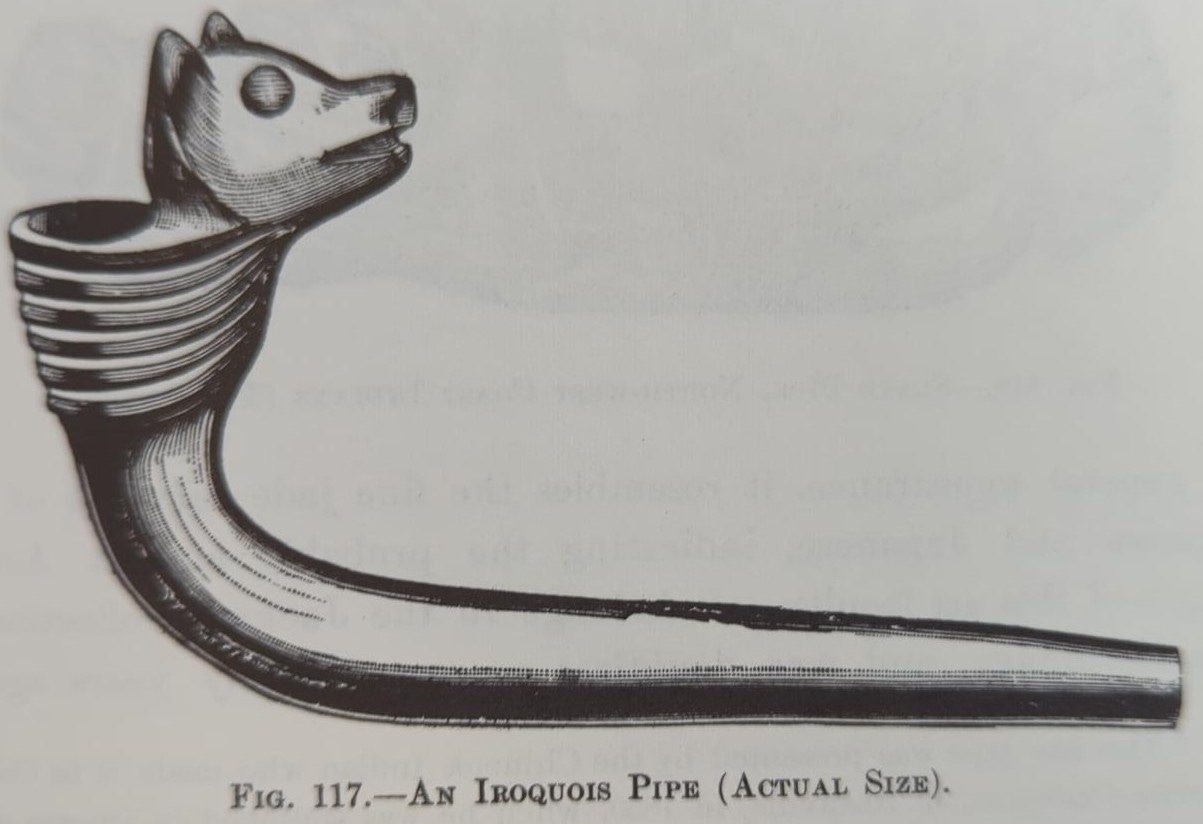

With some of the historical questions out of the way, let’s dive into some of the practices of the Stone Grave Indians. For one thing, they loved tobacco. Their pipe-making was actually of a rather high level. Many of their pipes were made of stone and would have required months to produce and as such held a very high trade value and place in the society. Water, sand, and slow drilling with a reed allowed them to bore holes in stone. I have included a couple of pictures below, one of a local pipe and the other of an Iroquois pipe.

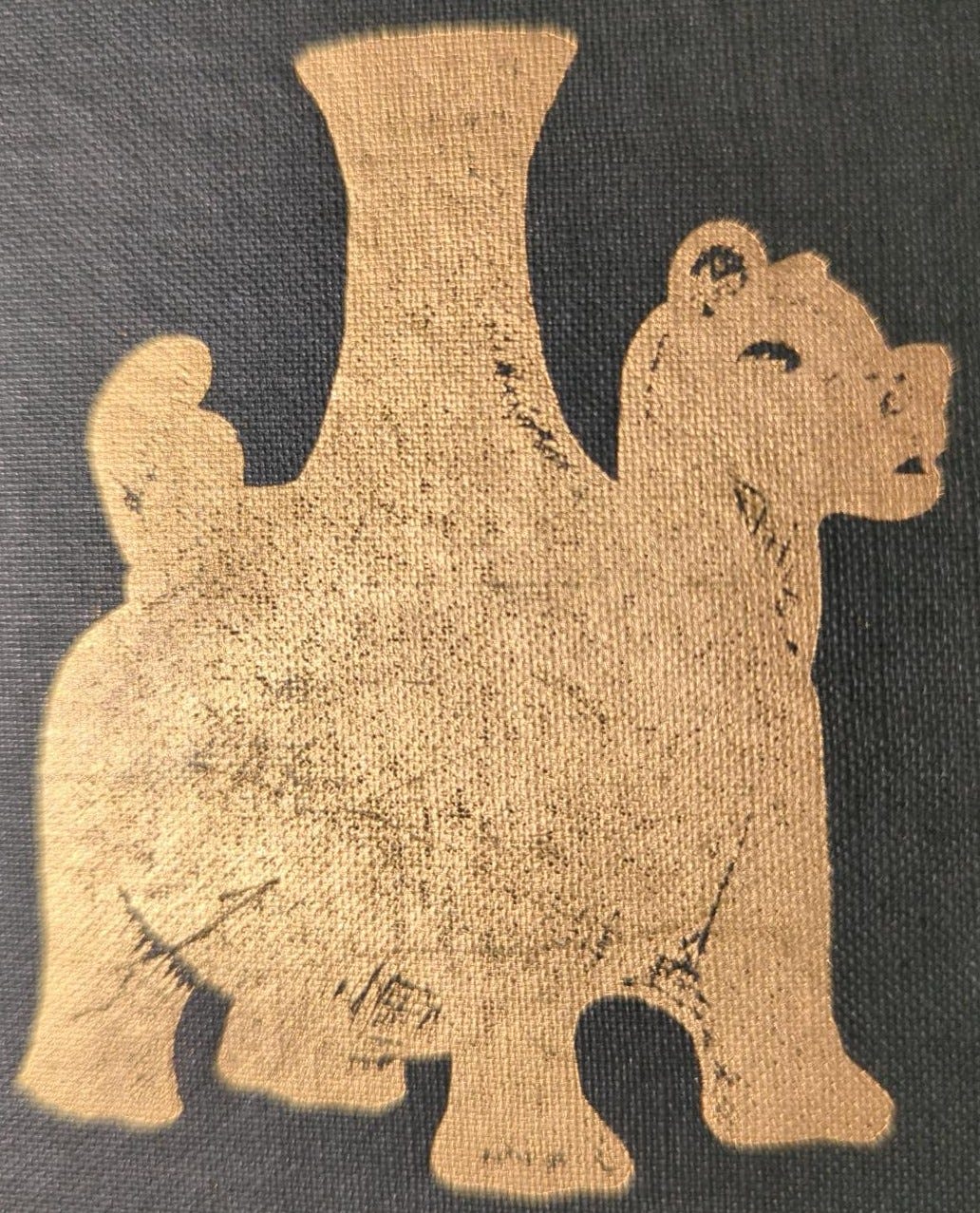

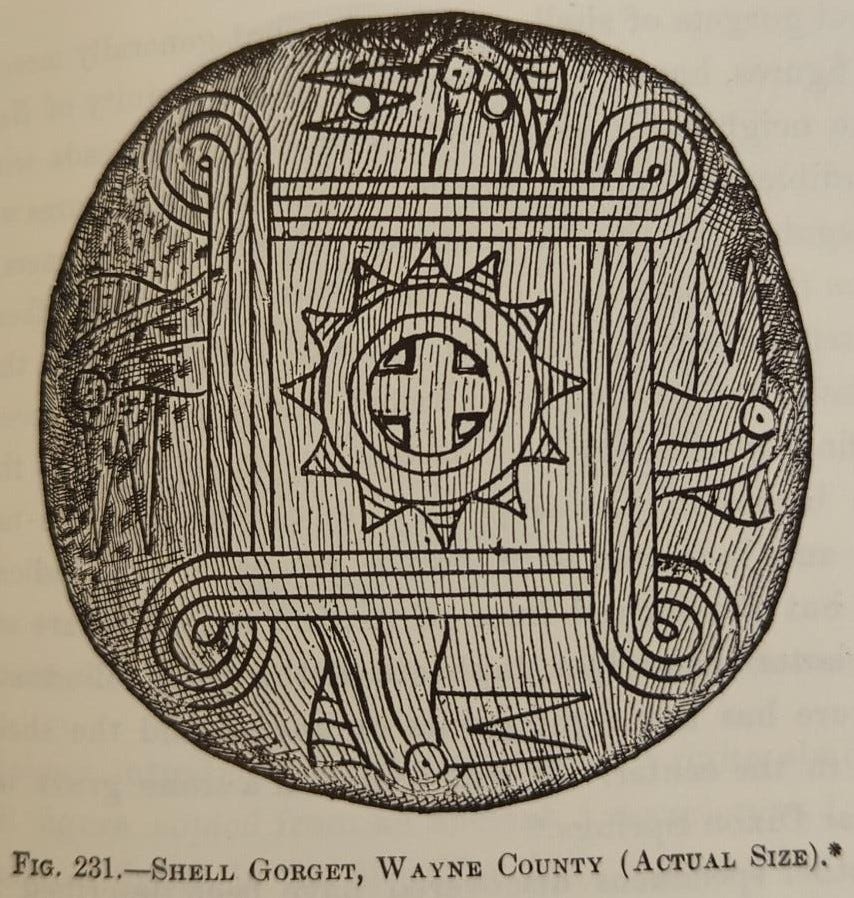

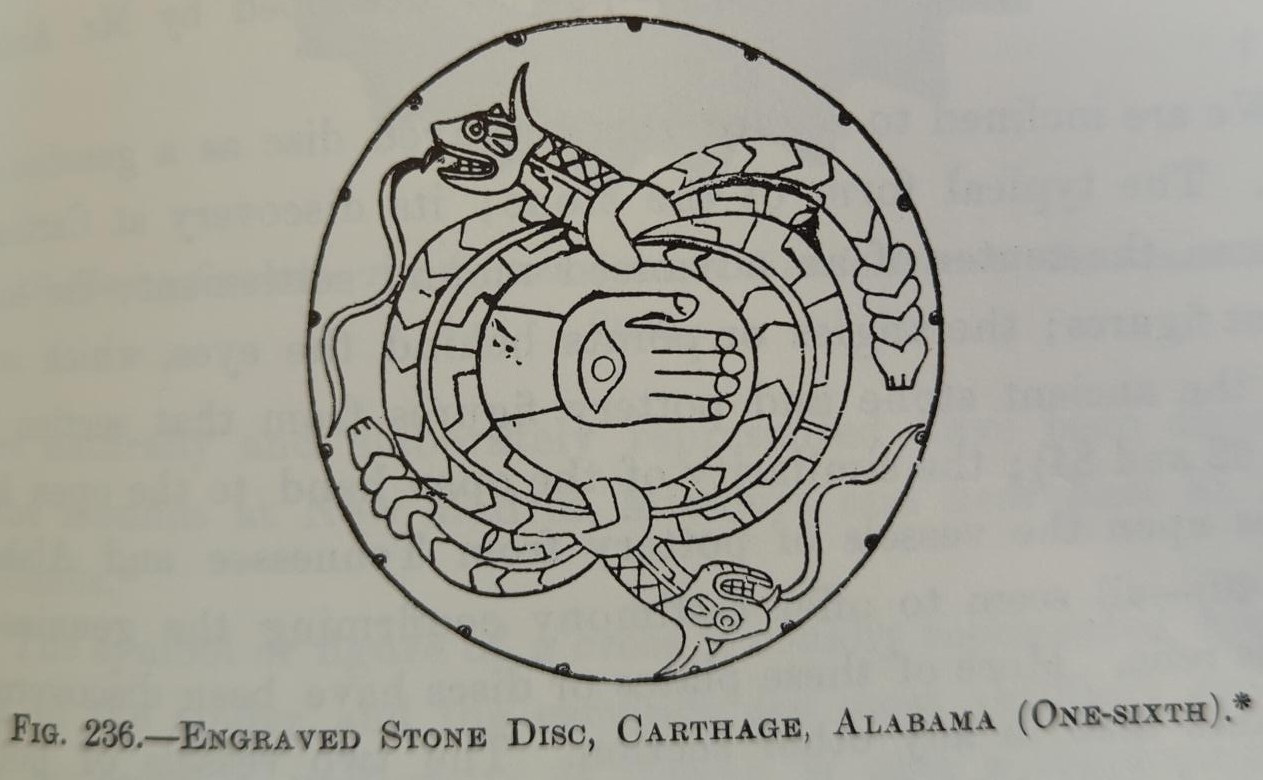

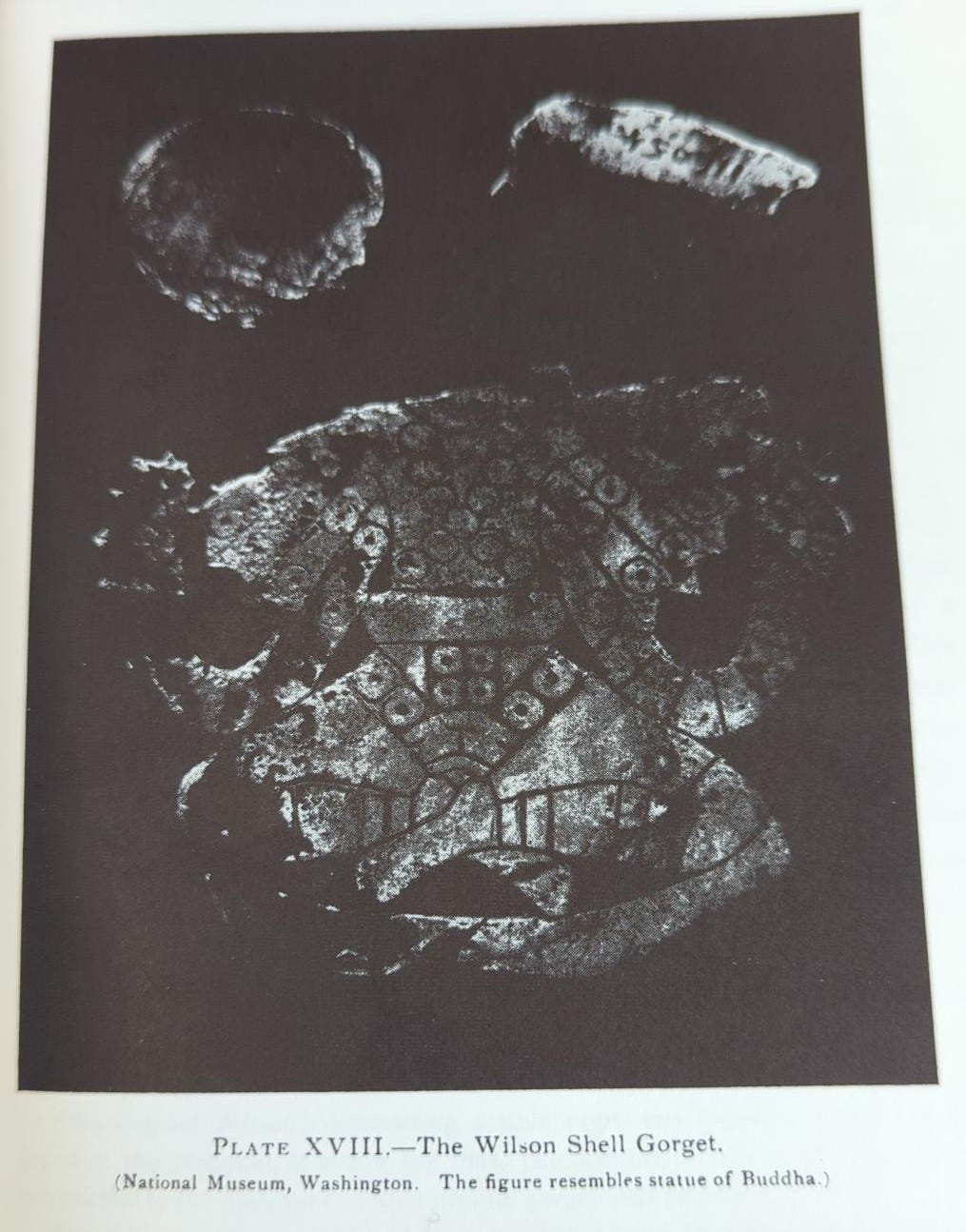

When it comes to Indian religion, many of them worshiped idols of some kind. Some of them worshiped the sun. Owing to some of their pottery and art, Thruston remarks that it could well be that they were of Asian descent long enough ago. They also liked to make images of turtles and serpents. One of the more confusing facts encountered by the Spaniards as they explored initially was that many Indians used crosses in their manufactured wares and art, though for what reason or what the symbol represented we do not know. I have attached four images below.

The first is of some of their cross and sun art, the third of their rattlesnake art, and the fourth is of a Buddha-like figure. Thurston is careful to note that the Buddha-like figure alone does not prove Asian descent, but mentions that at the same mound there were Eastern Swastikas found. This got me curious. In fact, after some further research, I found a BBC article with Navajo art that looks quite similar to our sun picture below. If we remember that the Southwestern Indians and this ancient Stone Grave people were related, perhaps that solves the cross mystery Thruston puzzled over as the crosses of the Indians could very well have been degenerated swastikas. One can see, even in this shell gorget, the move from the swastika symbol to a cross-like one from the Navajo art piece, though it maintains some of its shape in the direction of the winds and the four birds. I have attached the Navajo example below the one from our own Wayne County for your consideration of my hypothesis.

Moving on from art, it should be noted that, for the most part, no metal ores were worked. There were copper pits nearby Lake Superior and copper from the pits did occasionally make it all the way down in trade to Tennessee. However, this was highly unusual. The copper ores of East Tennessee were not as malleable as those of the Lake Superior pits. As such, many stone implements were used. Most people are familiar with how these implements may have looked, so I will not include photographs. The chipping process also would have taken some time and required care not to shatter the piece. Pieces of bone or horn would have been pressed against flint or jasper for careful flaking and eventual shaping. Thruston also notes that since many of these pieces were fragile, stone implements were usually relegated to ceremonial dress and less demanding work.

Returning to the topic of sea shells, they were not merely used in trade. In fact, many sea shells were used as utensils. When these were not available, pottery was made that modeled the shells. In their state of semi-civilization, the Stone Grave people used cooking utensils. This follows a wider pattern set out by Thruston of questioning what their society would have looked like if they had not eventually disappeared.

Another subject touched upon by Thruston is the games played by the Stone Grave Indians. In some graves, marbles were found. This seems to indicate that the Indians played marbles, though they also could have an unknown use. He also discusses a game that Adair called tchung ke. It involved rolling a stone disc with a pole and not allowing the stone to be hit by an opponents poll. The play area would have been mostly flat and involved pairs or sets of pairs, one to roll and one to try and hit the stone.

I will not spend any more time on Thruston’s archaeological observations. Largely, the work is examining only what has been found in graves. So, there is a limited amount that can be discerned and applied when trying to learn about pre-colonial history or anthropology. If you are interested in learning more about pre-colonial archaeology I very much recommend the work. Thruston seems well measured in his inquiry and on a couple of occasions derides uncareful examination of the graves. Undoubtedly this is still a decent resource.

Thruston in the Context of Our Book List

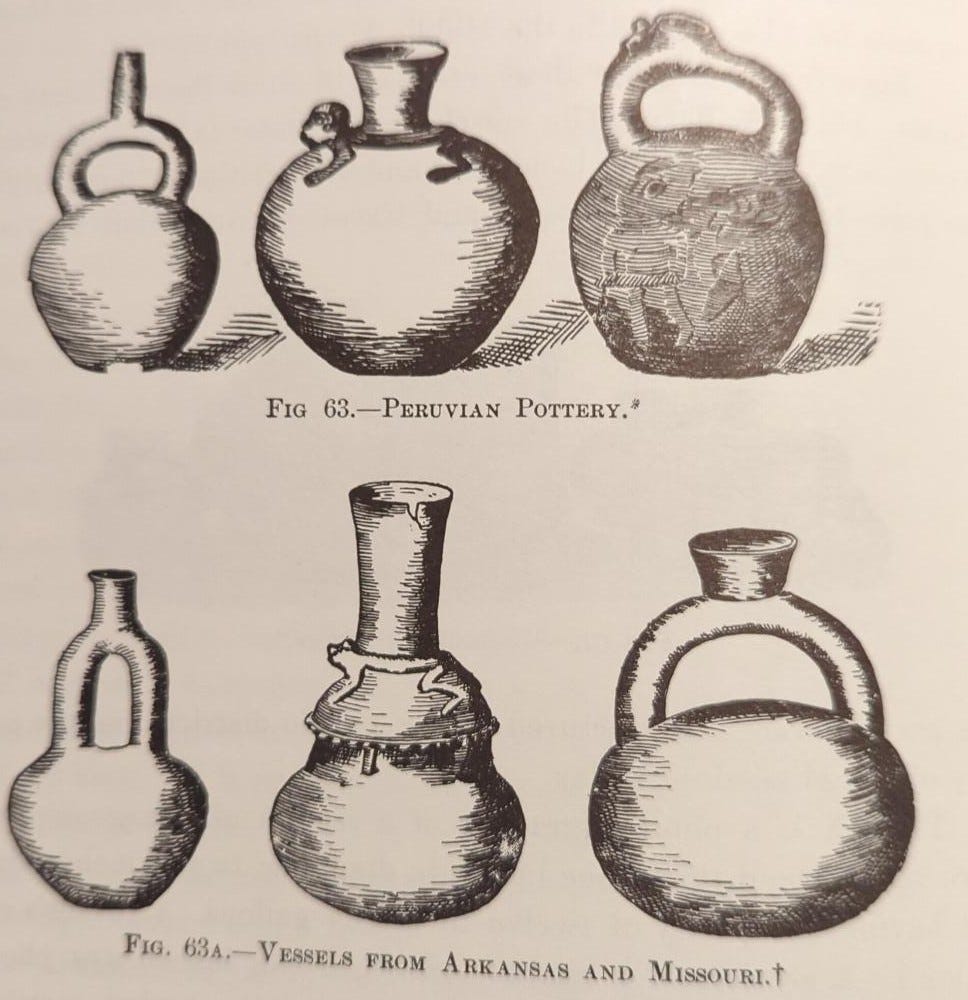

Gates Thruston makes some observations that provide context for the other articles that I will be releasing or have released. For instance, in my article on Joseph Bishop, Bishop mentioned a salt lick. I could not find what that referred to. In discussing some pottery which the Stone Grave Indians used, Thurston points out that they had vessels for boiling salt water for salt, featured below. He had found some vessels near the “Sulphur Spring” or “French Lick” at Nashville. A footnote reveals that many salt pans had been discovered in Southern Illinois near the Saline River, which very much reminds me of Mr. Bishop. There were also salines near St. Genevieve, Missouri and mentions of such things in accounts from the French in Louisiana and De Soto in Arkansas.

Another figure referred to by Mr. Thruston is John Haywood. I have not yet gotten to Mr. Haywood’s works, other than my digitization, but will eventually. Thruston occasionally takes a negative view of Haywood’s historical work, as he believes that Haywood does not distinguish between fable and real event. For instance, Haywood wrote in one place that the remains of pigmies had been found near Sparta, but that this was incorrect not only for Sparta, but for the state. In another section, he disputes Haywood’s opinions on “stone trumpets” found on page 210 of his Natural and Aboriginal History and his insistence that the Indians were once . . . Israelites.

Concluding Words and Notes on the Project Going Forward

It should also be noted that Thruston cites De Soto’s expedition repeatedly, such that I will not describe each of his citations here. His observations on the complexities of pre-colonial life amidst all of the university narratives is well worth consideration. This leads me into the future of the project. Because I am writing these articles from library books, those must be prioritized. As such, my next couple of articles will be like this one. I will cover some of the accounts in Williams’ Early Travels. I then intend to do a biographic sketch of Abram Ryan, the “Poet of the Lost Cause,” as he was a known, albeit unofficial as far as I am aware, chaplain to the Army of Tennessee and was a parish priest at Immaculate Conception in Knoxville.

After that, I would like to do some more work with a more popular appeal. I have in mind the Bell Witch and the Battle of Athens currently. Some friends have inquired about the TVA, and I have acquired some resources for that, but that will be a larger project than I thought and may not happen for a few months. I have also been asked about folk tales, and that will require further research, though I have some materials to examine the life of David Crockett. As far as the 20 Tennessee books list goes, I will try to continue with the early accounts, such as the work of Allison or Carr or Guild, this year. It will certainly take some time to go through.

These are, of course, mostly one-off projects. However, I have one big project that I’d like to do this year. Nobody ever talks about the South’s role in the American Revolution. I intend to take Draper’s and Williams’ works from the list, and then take other works like those of Crawford, Lumpkin, and Alden, and even other works on John Sevier, Francis Marion, and Samuel Doak, and contextualize Tennessee’s place in the war. That will be a large undertaking and may take some time to produce. Furthermore, I am in talks with a friend to potentially get a recording system set up so that I can, in some way or another, make these posts audible and potentially expose more people to this history. If you have anything that you’d like to learn more about, let me know.

Antiquities of Tennessee by Gates P. Thruston